A story of that night haunts my imagination since childhood. The musky scent of creosote and beer, a towering saguaro aimed at the heavens. The grim shadows of a mesquite tree splayed across her bloody skin, her flowered blouse, swimsuit and rubber thongs. In a desert wash east of Tucson, 15-year-old Alleen Rowe was raped, strangled and beaten in the head with rocks. None of this could be stifled.

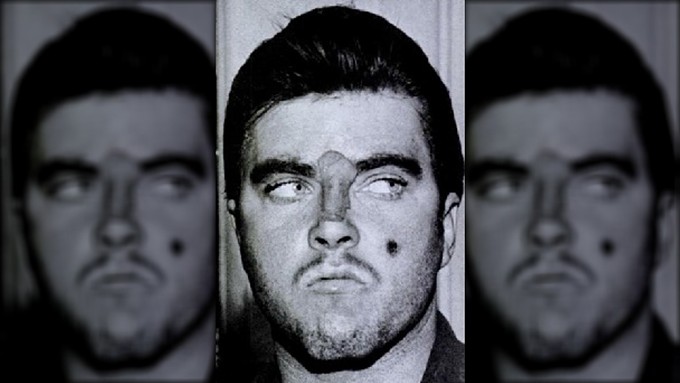

These are basic facts: Charles Schmid Jr., “The Pied Piper of Tucson,” and John Saunders, his 19-year-old cohort, murdered Rowe in May ’64. Mary French, Alleen’s 19-year-old neighbor and friend who was in love with Schmid, heard the screams from the car. She helped dig Rowe’s grave. Schmid’s desire to simply “kill someone” was fulfilled. Little more than a year later, Schmid strangled his girlfriend Gretchen Fritz and her 13-year-old sister Wendy in the living room of his house on Adams Street, after they’d gone to a drive-in movie. He dumped the girls on a desert hill off Pontactoc Road north of River Road.

I was just born when the Charles Schmid Jr. murders shocked Tucson in the ’60s. But Alleen was close to home. She lived with her mother in a house similar to ours, about a mile away; the post-WWII red-brick housing, the Our Mother of Sorrows Catholic church, a McDonalds at 22nd Street and Kolb Road.

When our family later moved east near Harrison and Old Spanish Trail, it was a walk to Alleen’s murder site. For decades the Pied Piper of Tucson disturbed me, even informed my sense of humanity and psychological connections. For one thing, Schmid was my introduction to horrific things one human could do to another. These people edged around my life from before my time, I could never have known them. But this was geographically close, and it lodged in the deepest recesses of my head. So, Schmid shaped the bleakest of ideas, like how unguarded innocence and trust could vanish as a young girl’s body met an unspeakable end.

It really started with creepy Schmid tales resonating on the schoolyard, taunts and wails of “The Pied Piper of Tucson will come for you, and kill you to the desert!”

As a child in the early ’70s, I’d struggle to sleep, and when I did, I’d fight off enclosures of Schmid nightmares: Schmid in his boots stuffed with rags so as to appear taller, the brutish distance in his kohl eyes, his face coated in base makeup, a fake Marilyn-style beauty mark. The feverish gestures of an unhinged sociopath attempting to purge his sickness onto underage teens. The last-moment horrors the girls felt as they stared into him. I had big sisters, and I would ache for their safety and well-being, and my own, alone in my bed.

Later, I’d think of Alleen’s shattered single mother Norma Rowe, a night nurse, who in a photo resembled my own mother when I was a child, and I assigned the same assets: pretty, protective, tender, loved.

And young Alleen. The fair-complexioned teen was a good student at Palo Verde high, wanted to be an oceanographer. Her up-to-the-moment style of the era showed blond hair in a short bouffant with swoop bangs. It was up in curlers the night she died, they flew off of her head as she was beaten.

Internal imaginings too: Had Alleen outgrown horse carousels? Did she whisper to boys, and did they appreciate there was something more they should try to understand? How did she pick and choose what’s important in her life? Did her books, music and friends allow her connection to an outer world? Did she cry out for her mother?

Alleen knew 22-year-old Schmid was a creep, she told her mother. She might’ve fallen under his spell, such as it was, as had many kids in Tucson bucking the squaresville world of mom and dad. Dozens of such kids knew of the murders and said nada. What an easy crowd to work down on Speedway Boulevard.

Ghosts should dim, over time, exhausted by their own energy. But lately, The Pied Piper of Tucson prowls my head at night as my wife and young children sleep feet away. Such childhood horrors resurface at the slightest sound, a javelina’s grunt in the yard or a eucalyptus branch brushing against the roof. In the light of day, it all seems so harmless.

The Pied Piper played up a deeper fear of the desert at a very early age. It’s cruel indifference to life, its spikey brutality and absolute wonder, of thorns and blossoms. Its unrelenting force hisses cautions: step gently, it will always have a story of death to tell. Who can count the barren stretches of desolation between life-giving oases? It is an absolute mirror of mortality. Say it to the thousands of migrants who’ve died in these deserts in search of a quality of life I was lucky enough to be born into. Here, we inhale the dust of the dead when we breathe. I cannot separate the desert from such truths.

The Sonoran Desert, after myriad hours of my life spent walking in it, respecting it, awed by it, being frightened of it, will always be a sort of spiritual haunting ground.

Some stories stay long and hard in all of us, color our perceptions, excite us, shame us, glare at us in the face. We all know the yarn: A relentless fraud develops a tremendous pull and adoration of teenagers, like that other Charles, Manson. (Curiously, their similarities are long: both given up by birth parents, a creepy narcissism and charisma and sexual tension for teens, a desire for stardom. Both tiny, stood around 5-foot-3 tall.)

In ’66, Schmid was sentenced to death. In ’72, the Supreme Court ditched the death penalty, long enough for Schmid to be taken off death row.

Schmid’s story has been covered to death, been anthologized, mythologized, and recreated. Don Moser’s great Life Magazine story hit me at a young age, and I dug Joyce Carol Oates’ short story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been.” Richard Bruns’ 2018 book I, a Squealer is a worthy read. Bruns, a former Schmid friend who assisted him in burying the Fritz sisters, later fingered him to cops. In the exceptional 2007 book Crossing the Yard, Richard Shelton recounted his work with Schmid in the prison system. Shelton, a gifted writer and UA English professor who died last year, was contacted by Schmid, a budding poet, and the professor began conducting writing and poetry workshops to help inmates express themselves. Shelton dedicated 30 years of his life to this program, and Schmid was its genesis.

Before Crossing the Yard was published, I wrote about a different prisoner who had participated in Shelton’s workshops. I asked the professor about Schmid, and he revealed that his initial ambivalence about working with a psychopath faded as the man developed empathy through writing and poetry. I was fairly stunned, thinking how Shelton must've suffered under the weight of the work, how he maybe started from a place beyond the reach of compassion. Schmid even changed his name to Paul David Ashley to distance himself from himself, but a frenzied attack cancelled all names. This month in 1975, two prisoners, “Dirty Dan” and “Sneaky Pete,” stabbed Schmid 47 times with knives, one a glorified can opener. Schmid, discovered in a pool of his own blood, his right eye speared out, survived another 10 days.

I was a boy when I heard Schmid died in jail, it did nothing to quell The Pied Piper of Tucson from hanging over my life.

Brian Smith's collection of essays and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections of La Frontera, based on this column, is available now worldwide on Eyewear Press UK. Buy the collection in Tucson at Antigone Books, 411 N. Fourth Ave. You can also pickup his collection of short stories, Spent Saints (Ridgeway Press).