It is a hot Thursday morning in May and a 7th-grade social-studies class from Dodge Middle Magnet School gather around Sidney Finkel, a living, breathing survivor of the most merciless mass genocide in history. His partner, 83-year-old Barbara Agee, stands near him, one moment attending to his appearance, tucking into his trousers the tail of his pressed white shirt, and another explaining to me how speaking events such as this one has no doubt extended the life of the 90-year-old man she adores.

They are inside the gated, tranquil courtyard of the Jewish History Museum, a skip from downtown Tucson. To the right is the airy Holocaust center, a hush-inducing, well-appointed hall of edifying tributes and remembrances, honoring genocide survivors and liberators. It is where the too-often unspoken is spoken.

In the center is the synagogue (Arizona’s oldest, built 1910), the museum’s home, now an educational center, is a Tucson architectural marvel, a formidable Ely Blount design of arched windows, Greek revival and hand-carved interior patterns rescued from ruin in 1998.

The Holocaust center’s primary focus is on survivors, such as Finkel, who have made Southern Arizona home.

In comforting palo verde shade, moments before the kids step into the Holocaust center to watch a wrenching 35-minute documentary on Sidney’s life, you can see in their tender faces, their carriage, their politeness, the evidence of good mothers, that these kids, of various colors — a true microcosm of Tucson’s population — have little idea what it feels like to be a dead-eyed, hollowed-out soul of yourself as a pre-pubescent child.

They soon learn Sidney (born Sevek Finkelstein) is a living miracle, and a potent reminder of the peculiar resilience of human nature, overcoming acute suffering and death, overcoming life-long traumas to arrive, finally, at a place of peace.

No, the kids don’t know, but can imagine from the film, what it feels like when German bombers fill the sky and blow up your neighborhood at 7 years old, people on fire, animals on fire. Losing your oldest sister, who was pregnant and smuggled out of a Jewish ghetto to a Polish Catholic hospital, only to be discovered by Nazis, who stormed in the hospital, tossed the baby out the window to its death, and murdered your recovering sister in a Jewish cemetery. How your parents unsuccessfully attempted to soothe you, while the world around you was literally a prison.

Or later to be torn away from your mother and she was crammed into a Nazi cattle-car train, with your other sister, who couldn’t bear to part from her, to a death-camp murder, telling you “You must be brave, son. You do everything you can to survive. You are our future.”

You “lucked out” because your much-older brother Isaac and dad Lieb had precious work permits that allowed them to stay alive a little longer as slave laborers in a factory, and you snuck in, because your older brother, who spoke perfect German, summoned life-risking bravery and bribed a guard who was whipping you, people’s blood and guts spilling around you.

To be so dehumanized by 12 years old, starving, forced to carry dead prisoners from their bunks and pile them up like lumber, as to be indifferent to the person you love most in the world, your father, who, when he discovers you after a painful separation, emaciated, near-death in the Buchenwald concentration camp, gave you his last piece of bread. You didn’t feel anything anymore, “incapable of feeling affection.’ That is the last time you see him alive. The guilt of that exchange haunts your entire life.

What the kids watching don’t learn is what it means to carry that same dead-eyed survival instinct into years as a father who used alcohol to deaden childhood wounds. The survivor guilt of six million who did not, including parents, aunts, uncles, sisters. And to wait nearly 50 years to tell a family member the story? How does one forge formative relationships after all your early ones in life are taken away?

Sidney and Barbara enter the room before the film’s end. For Sidney, it is too painful to watch.

The two-dozen or so kids sit cross-legged on the floor. They listened hard, so still during the screening, their shifts in positions are audible during quiet moments, and a few wipe tears. A teacher from the school weeps in back.

To their right, a gallery wall of faces, small photos of survivors in Southern Arizona with accompanying words about each. Too, photos of murdered relatives of the survivors. It’s a pictorial narrative that asks the eternal question: what might have been?

After the screening, Lori Shepherd, the museum’s executive director and host today, addresses the children with echoes of Elie Wiesel, “When you meet a witness, you become a witness. Right?” She brings Sidney up to talk with the kids.

Sidney’s mere presence shifts plates of time to the present, from deep tragedy to something else entirely.

The kids surely have difficulty believing this old man from the film, standing before them, is the one who survived the unspeakable, six childhood years spent in Jewish ghettos/annexes and imprisoned at Czestochowa, Buchenwald, and Theresienstadt concentration camps. It is hard for anyone to imagine.

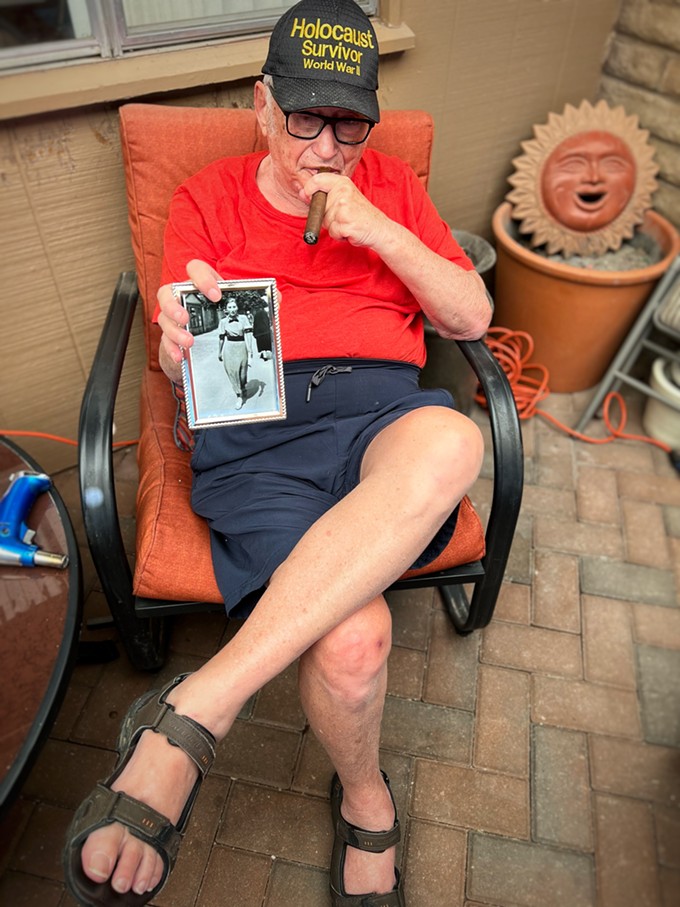

Sidney moves from a chair in the back, wearing a black ballcap that reads “WWII Holocaust Survivor,” and gray trousers. He takes the wireless mic and stands before the children, is self-effacing, jokes about himself. Introduces his partner Barbara, how they met on a dating site as very old people, and they play off each other like some classic Burns and Allen skit. The kids likely don’t realize Sidney employs humor to shift the room’s ominous sadnesses into another realm, one of redemption, hope, kindness. It is a sly move from an old storytelling master. It’s no wonder he got an honorary doctorate in literature from St. Xavier University in Chicago in 2011. A guy who earned his GED in his mid-50s. He tells the kids how he was saved by a German educator and teachers from a school in England just after liberation, he learned to read and write.

The kids pose thoughtful questions filled of wonderment and later take pictures with the man, group shots, selfies, even separate with his partner Barbara. That kids want photos with Barbara is a surprise: “That’s never happened to me before,” she says.

Earlier, seated on a pew beside Barbara in the synagogue, Sidney told me the first stage of denial: “a psychologist told me at 14 to try to forget it. Everybody said that. Just forget it.” Took him 50 years of holding in the worst human pains imaginable to finally let it out.

* * *

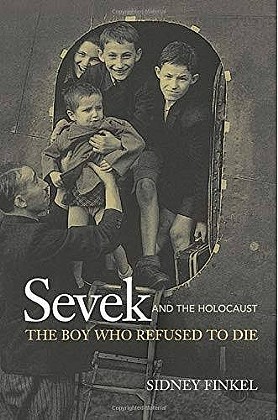

Sidney’s memoir, Sevek and the Holocaust — The Boy Who Refused to Die, upon which the documentary is based, is a highly readable, heavily fact-checked and well-edited chronicle of his early life as a Nazi prisoner and how he survived. He describes the closeness he felt to his family members. The smart, compact writing, in the boy’s POV, does not dwell in sentimentality, or victimhood, nor use any kind of sympathy device. It doesn’t need to. It’s almost like he’s sharing his story around a campfire, albeit a grim one. Nobel-prize winner Elie Wiesel, author of Night, provided a cover blurb. The two were imprisoned in Buchenwald at the same time.

It is the same tone and manner he has expressed to assembled academics at universities, to young adults at museums and tributes, to middle-schoolers, to Air Force bases, all over Tucson, the country and world, since around 1994, after a visit to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum with his daughter and son.

By the end, the book becomes a kind of meditation on what the abominable experience of the Holocaust taught Sidney later in life; self-reflection, gratefulness for family, a sense of acceptance, and kindness, with notes from his son Leon and granddaughter Rebecca. The book is easily found online.

He says the actual writing was fairly easy, “it just came out.” He adds, “I think even when an anti-Semite reads this book, they like him (Sevek), they’ll have a favorable viewpoint of Jews.”

He, and his family, worked hard getting the book out. “You have to talk to teachers, schools,” Sydney says. Such work paid off—with no big-publisher PR team, it earned great reviews in key places. It sold on reputation alone. Schools around the country have read his book as a part of their curriculum, and Sidney reckons he’s sold close to 30,000 copies since first publication in 2006, an incredible number for what’s basically a self-released book. If a classroom can’t afford the books, sometimes he gives them away, or, say, a doctor friend will subsidize a school purchase. His daughter Ruth has taken over management of the work, and Sidney will leave it to Ruth Finkel Wade and son Leon Finkel to carry on when he dies.

Another book, the just-released The Ones Who Remember — Second Generation Voices of the Holocaust (Simon & Schuster), a collection of essays by children of Holocaust survivors, was co-researched and compiled by Sidney’s daughter Ruth, a retired Domino’s executive, who is now a speaker and docent at the Florida Holocaust Museum. She also assists her dad with his book and speaking engagements. The book features a beautifully written essay by her involving the emotional disconnects of growing up with a Holocaust-surviving father. It’s a lovely story of reclamation that makes the book worth seeking out.

A third tome, the excellent The School that Escaped the Nazis (PublicAffairs) which is released stateside next month by British journalist and author Deborah Cadbury, tells the story of the co-educational boarding school, Bunce Court, which educated, among others, traumatized Jewish children who had survived concentration camps, or survived hiding in Nazi-controlled central Europe, and Sidney is featured.

* * *

A few days after the film screening, in the quiet, cozy front patio of the couple’s immaculate three-bedroom home in Oro Valley, northwest of Tucson, Barbara sits adjacent to Sidney, in patio chairs. He works a stogie, which he holds close to his mouth, and peers over as he talks, as if he’s searching for something.

At 90, Sidney's confident manner is like what would result if you crossed Peter Pan with a nonagenarian bingo player on a winning streak. He is a savvy, smart guy, armed with a gentle charisma; routes to instant likeability. I can’t help but wonder if any of those qualities helped him skate through difficult situations earlier in life, or address the things difficult to psychologically absorb. He’s told me more than once that years ago he got over feeling like a victim.

“I never knew what the word ‘victim’ meant,” he says. “I just had to get on with my life to earn a living.”

Yet, just having the wherewithal to tell his story, after decades of keeping it to himself, affirmed his life. Too, his book, his lectures (there is even a school garden named after him in Arkansas) can translate into a kind of worthy hero figure, underpinned by unrelenting tragedy.

Sidney knows this, laughingly calls himself a “little c” (little celebrity) for having emerged as both an influential and necessary international speaker on the Holocaust. He enjoys the attention. He has more than earned it; hell, he is more deserving of such than the vast majority of people pedestalized in our culture.

Barbara has witnessed this, favorable situations later in his life. Barbara tells a story of how Sidney scored a doctor’s appointment to treat a painful, ongoing case of acid-reflex, avoiding a months-long wait by scanning a list of doctors and picking one with a Jewish name, and then explaining to that doctor he was a Holocaust survivor.

“I was flabbergasted,” Barbara says, with no hint of irony.

In person Sydney is kind, so accommodating as to make one almost nervous. He’s the same with teachers, students, museum workers, and among other Holocaust survivors.

His partner Barbara is too.

Theirs is a late-in-life new love, blossomed almost eight years ago after meeting each other online. It is not without the difficulties and personal navigation of two people, each saddled with their own baggage. “Here is Sidney,” Barbara says, “who spent most of his life married, and me, most of it spent single.” She adds, “I came with baggage.” She looks to Sidney. “And he, of course, came with bigger baggage!”

Sidney chuckles along with that one.

She references the noticeable purple birthmark on her face, which made for a life of insecurity; as a girl she was taught to cover it with makeup, which led to a bigger idea that she had to cover things up to be accepted. Her birthmark is a bigger metaphor now: “I wanted to do more uncovering. The covering up early, had me uncover later in life.” She looks to Sidney, adds, “I wanted to uncover this intimate, close relationship.”

They reach over to each other. He kisses her hand.

“He’s knows my triggers now, and will often respect those things. When he could’ve hit the trigger he didn’t.”

Barbara winks at me several times in precise moments of candor. She’s cagey, curious and knowing, her sentences thoughtful, straightforward. She knows a lot more of the world around her, an accumulated wisdom, than she would ever reveal. She calls herself an “adventurer” to Sidney’s “homebody.” To hear her, it is understood that when moments in her life were not fun, they were interesting. She is shy, not a fan of attention. Her voice is full-on grandmother, warming, almost musical in cadence, usually punctuated with a chuckle.

She has no children and endured one bad marriage back in the mid-’80s, which lasted a year. She was born in 1939, Mom was a teacher into the arts, Dad was a lumberman, “a high-bottom alcoholic.” They’d take the jeep out, go hunting, fishing, logging. Mom took her to plays. “I had an unusually broad childhood for being raised in a town of 5,000.”

She remembers Life Magazine pictures as a girl, “horrifying images of the Jewish side of the Holocaust.” She soon read Viktor Frankl’s holocaust survivor tome Man’s Search for Meaning and it had a big impact. “Never in her wildest dreams would I have imagined I’d be with a survivor of the holocaust,” she says.

Barbara talks about their differences in value systems. She being the more diplomatic one. “Sidney, on the other hand,” she laughs, “says just what’s on his mind and sometimes that’s not very diplomatic.”

He nods, “Two rocks rubbing against each other until a diamond is made.”

Barbara earned a masters in nursing, with a focus on gerontology. Got into teaching as well as practicing lots of different kinds of nursing. Landed in Yuma, Arizona to teach, the UA in Tucson, NAU in Flagstaff, returned to Tucson (“I love to hike!”) for good around 1990 to teach and worked home health and hospice here.

The couple talk freely of their relationship, becomes witty banter.

“The gerontology helped with my sexuality,” Barbara says.

“I picked well!” Sidney interjects.

“My counselor does say we are very unusual,” she adds.

Sidney: “We made love on our first date!”

“No, not our first date!” Barbara, embarrassed, adds.

“Okay, maybe you’re right,” he laughs. “But it was right away”

“She doesn’t cook for me,” Sidney says. “For dinner I eat a hot dog and three pancakes.”

“He’s not a fan of greens,” Barbara adds, “and I am. He never has been since throwing up grass, which he ate to survive as a boy.”

A younger friend of Barbara’s had introduced her to OurTime dating site. “I’m looking, thinking what do I want to do for the last part of my life,” Barbara says. “I guess I wanted a partner. But I didn’t need a partner.”

He went online, three different dating sites. “I was in Chicago talking to different ladies in Tucson. I had choices. Barbara had all the qualities I loved. The way she spoke; she is highly intelligent. When she feels something is wrong or right, she is probably right.”

“I don’t do too much fetch and carry for him,” Barbara grins, and looks at me. “I wanted you to know that.”

Barbara had just completed a journey across the country when they met, living in a travel trailer. “I didn’t have a lot of money because I had an adventurous lifestyle.”

Even after they were a couple and Barbara moved in with Sidney, one woman from a dating site wouldn’t stop calling.

Barbara scoffs at the gall of the woman. Sydney nods along.

The pair didn’t marry, didn’t see the point, instead call each other “lifetime partners.”

For outside approval, Sidney says, “My son Leon came for dinner. He’s a lawyer, and he gave me the thumbs up on Barbara. And if he wouldn’t have, I would’ve listened to him.” He pauses. “Funny, a father listening to his son.”

Sidney has moments of long quiet depression, for which he takes supplements. He tells of clinched fists and tears in his eyes, and waiting for it to pass. He tells of things hanging on, his mother for whom he still “has great longing.”

“Sometimes I’m really brave enough to ask him what’s on his mind,” Barbara says. “Other times, I know later he will often offer it.”

The couple engage in gratitude meetings, just the two of them, and count the ways. They go on picnics.

“Sidney’s my big growth opportunity,” Barbara says.

He turns to her, says, “Can you tell when I’m depressed?”

She nods. “Hmm, hmmm.”

Love is work, regardless of wisdom, age. Each go to counseling, as Sydney has done for decades. A few times they visited each other’s counselors together.

A central question is how does one forge formative relationships after most of the early ones in childhood were taken away?

Sidney is still learning. For example, the separation anxiety. Barbara found it difficult to leave Sidney to go on trips. Barbara is well-aware of lingering childhood abandonment traumas.

“I would think she was never coming back,” Sidney says. “I would say, ‘Why are you leaving me?”

“He could hardly believe I’d come back,” she adds.

There is a paragraph in Sidney’s book, where he is crammed into a death train “like sardines” en route to a concentration camp. He is separated from his father and brother, and in a fetal position, a boy, the first time he is ever truly alone in the world.

“Crippling fear entered my body,” he writes, “fear that would stay with me for the rest of my life.”

He agrees with that now. “It hasn’t gotten easier,” he says. “I just deal with it better.”

* * *

In 1945, the British government allowed a number of child WWII refugees into England. Sidney was luckily picked to attend Bunce Court in Kent, England, a private boarding school co-founded by heroic educator Anna Essinger.

Sidney arrived at the school as a Polish-speaking orphaned Nazi concentration-camp survivor, and the school saved his life. It is where he learned to be human again, gain insight to a few of the wonders of being a prepubescent kid. He arrived at boarding school not knowing the alphabet, and the curriculum inspired him to become an avid reader. He regained some empathy.

The teachers would not give up on him. “They loved me until I could love myself,” he says. “I learned English, it was wonderful.”

He was always near his big brother Isaac, until the day he boarded the ship to America. The Nazis could not take that away.

A surviving uncle in Chicago sent for him. He got his visa and arrived in 1951, filled with a sense of American promise.

He searched for such promise in ensuing years. “I didn’t have any home, lived a lodger in people’s homes. Rented a room.” He married, a union that bore two children, Ruth and Leon, and divorced. He married again to Jean, which lasted well over 40 years. Jean had two young children, and the couple bore Lisa. Sidney now has five children and 10 grandchildren.

Jean was diagnosed with cancer eight years ago and 15 days later she was dead. “Worst pain I ever knew,” Sidney says. After long pause, he adds, “worse than the camps.”

He is proud of his children and grandchildren, pictures of them adorn their refrigerator, and he talks at length of their accomplishments.

Sidney offers brief, almost contrite-sounding responses when talking of his first-born children, from his first marriage, Leon and the elder Ruth. He was shut down, he was drinking. How it took nearly 50 years for him to come to grips with his personal history and share it first with Ruth, then others. He got sober first, and he credits AA for saving his life there, allowing him to reach a point of self-reflection to figure out who the hell he was.

“I was in AA more than 40 years. The love and acceptance. That was the most influential thing in my life. All my friends were in AA. I would’ve lost all my kids. It gave me confidence to buy a building, to speak in front of people.

“Jean was instrumental in me joining AA. She was an alcoholic too who got sober before I did.”

He lived in Homewood-Flossmore area on Chicago’s southside. Sidney worked for the same company for 40 years, Polk Brothers appliances and electronics in Chicago, a manager. He was the oldest employee. “They gave $22,000 when they went out of business.” He’d also purchased an apartment building, for $200,000, and sold it 20 years later for double.

“I had obligations to both families.”

He and wife Jean chose Tucson because they loved it here, would split time with his home in Chicago, and his sister Lola had lived here, in this same house, until her death in 1999. Lola survived the Holocaust, but was beaten severely by Nazis and Sidney says, “was very troubled.” Her son, Luke, was born developmentally disabled at the tail-end of the war. “My brother-in-law rushed them to a hospital and saved their lives.”

Sidney is Luke’s guardian. He would often visit him in the Chicago care facility, “holidays, Christmastime,” until COVID curtailed their visits. Barbara fell in love with him too. She later produces a heart-bending book Luke created, including pictures of family and tributes to his favorite classical composers. “Luke is kind of a savant, especially with classical music.”

Sidney also receives a German pension. “The German government has been very good to survivors,” he says. “It isn’t much, less than Social Security, but it really helps.” That included lump sums a few times in his life, and a monthly stipend. He’s been receiving for decades, after much paperwork and a proof process.

“We have to write in, notarized letters to let them know Sidney is still alive,” Barbara says.

* * *

Barbara steps inside the house and returns with pictures of Sidney’s wife Jean, taken in Chicago. “When I first got together with him,” she says, “it almost felt like Jean was there with me. Helping me. It felt supportive.”

He talks of his bladder cancer, which he’s had for seven years, and which forces him to excuse himself several times in conversation to the bathroom.

“The doctor says,” Barbara adds, while Sidney is stepped away, “he will probably die of something else besides the cancer.”

Sidney returns to his perch, relights the cigar, and knows exactly what was said, “If I died today, I would be good. I made it to 90!” Yet Sidney appears to be acutely aware of his own mortality. “She’ll be fine,” he adds. “When I die the house is hers forever.”

(“He says that a lot,” 83-year-old Barbara tells me later on a phone chat. “I don’t have strong feelings about that. We’ll see. I wouldn’t be surprised if he outlives me!”)

“This is the happiest time of my life,” Sidney adds. “We have enough money, we have everything America can offer.” He learned to swim at age 70, the couple hits the pool a few times a week.

“It wasn’t all bell and whistles. We’ve grown to really love each other,” Barbara pauses, “I didn’t want all the bells and whistles. That’s just exhausting.”

Sidney nods.

She adds, “I never thought I’d be a grandma,” to which Sidney says, “My family loves you.”

* * *

At the end of Sidney’s film, he is inside the Buchenwald Concentration Camp, one of two visits where he appeared as an honored guest, and speaker, on Nazi liberation anniversaries. He is standing in the grim spot where he last saw his father alive. He prays out loud to him, surrounded by family.

“Here I am with your grandchildren … I can see you smiling, how happy you are to see that I survived and you have these wonderful grandchildren.”

Before our afternoon ends, Sidney offers, “I didn’t think that much of myself.” A moment passes, he adds, “If there was no Holocaust I would’ve done great things.”

Barbara is aghast, and she says to him, “Look at all the great things you’ve done!”

Brian Smith's collection of essays and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections of La Frontera, based on this column, is available now worldwide on Eyewear Press UK. Buy the collection in Tucson at Antigone Books, 411 N. Fourth Ave. You can also pickup his collection of short stories, Spent Saints (Ridgeway Press).