Her living room is hyper-cozy, crammed with books. They’re everywhere, on shelves, on tables, towering in piles on the floor and in boxes. She apologizes, explaining they are in the middle of a home renovation. The affair, inside this ranchy, mid-century home, which she has shared with her husband Jack for 31 years, is overseen by lovely fine art and photography. One piece, a black, charcoal and graphite abstract by Tucson artist Josh Goldberg dominates the room. The work is telling, all murky crevices, unreal tusk-like arches. A quick study offers a manifestation of deep melancholia, or emotional trauma. I say this aloud and she agrees. For her it’s a reminder of the Holocaust, some connecting and consistent nature passing through generations, and how it assumes shapes of necessity. It’s almost circular that way.

“Isn’t that the dilemma of life?” she says. “Sometimes I just sit and stare at it.”

She relaxes into a deep reading chair, wearing a black tunic and long black skirt, yarmulke, and a coral red beaded necklace. Her chestnut bob features bangs, which match her youthful-sounding voice and expressive eyes, a whimsical balance to her refinement. So it is no surprise when she prefaces topics with “You’ll love this, this is great!” Or, “I have to tell you something interesting, I still can’t get over it.”

I’m to the side of her peculiar collection of artful snow globes on the coffee table before me.

Within minutes I learn a conversation with Rabbi Stephanie Aaron never clots into meaningless din. She’s effusive, to be sure, sometimes it’s as if her burst of sentences cannot contain the theories and thoughts that went into their construction. Art, literature, geography, morality, world religions and Judaism as foci pile atop each other, and circle back connected, often as metaphors placed into a larger human context and peppered with self-deprecation.

At one moment I wonder if ever there is an off lever to her running monologue. I later ask her husband Jack about this, and he laughs. His response comes after a long thoughtful moment: “Well, everything she says is interesting!”

Aaron is obviously an educationalist who communicates through storytelling. In this almost peculiar, intuitive way, she can soothe your center with an understanding worthy of a good therapist, and in show-not-tell narratives, her theses often ignite with personal meaning. An example: She relates a story of helping a kid years ago whose aunt was a Holocaust survivor who’d been cremated.

“One of the kids said to me, ‘This is illegal. But my aunt was a Holocaust survivor and I wanted to bring her.’”

They were in Warsaw, Poland and walked over the Vistula River with the aunt’s ashes and released her out over the river.

“I knew right then,” Aaron says. “I felt her peace. That was the first time it was a Holocaust survivor … It was unexpected. But I came to understand. Others have said, ‘This is what happened to my parents and I want this for me. They’d say ‘My parents didn’t choose that, I want to be in death, the same as they were.’ It is not a Jewish custom to cremate,” she adds. “Other rabbis don’t do it.”

To hear the rabbi explain it, her words widen any context of cremation, and it becomes a story of reclamation, telling of a wider family, of parent-child relationships. Had me grateful for the tender tentacles of dead family members, whomever that family may be, friends, aunts, parents; how they drift around in the recesses of daily life, orbiting houses, inhabiting trees barely in sightline, an energy that never slackens.

She salvages people, places, things, even the actual Torah used at her synagogue was rescued from the Nazis and is still being restored from WWII.

As a rabbi, she’s had her hand in myriad projects, an endless cycle of human services, all of which she deflects back to those served: from building a house with Habitat for Humanity, to connecting wayward offspring of Holocaust survivors to bigger families, to placing food and water on migrant routes from Mexico to helping displaced families from other countries find sanctuary. There is the Butterfly Trail, a remembrance of the million and a half Jewish children who were murdered during the Holocaust, which Aaron helped to connect in Tucson. Holocaust survivors I’ve met in Tucson revere her, their partners, children and grandchildren too.

The salvaging has extended to Nazi paraphernalia.

“Listen to this!” she says. “I’m a third-generation Rotary. Yes, I’m a Rotarian. Maybe 10 years ago, a non-Jewish woman tells me she had been cleaning her mother’s attic and found a huge Nazi flag.”

The woman’s father helped in a liberation of Cologne, Germany.

“She asked me, ‘What do we do with it? My brother wanted to sell it on eBay.’ I said, ‘I’ll take it.’”

She took it home and spread it out with her husband Jack, also Jewish.

“It felt like pure evil,” she continues. “If you could’ve seen the workmanship. The gold tinge, the multi-colors. The contrast of this magnificently crafted flag to such mass-destruction, the death and the slave labor that went into creating it. It was all there.”

It made them sick to have it in the house. The flag wound up in the Jewish Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C.

Salvaging extends to literature.

In a culture where so few read anymore (“we don’t read books, we read excerpts”), in an act she calls “subversive,” she started a book club through her synagogue. The book club’s first assignments involved going back 100 years and reading Jewish authors by decade, fiction, non-fiction, the gamut. “Appreciating literature, that’s an underlying theme of my work.”

Rabbi Aaron is the spiritual leader of congregation Chaverim (means “friend” in Hebrew), a small Tucson synagogue whose membership boasts 100 families. It is an impartial, liberal Reform congregation, LGBTQ+-friendly. She has been there 30 years, working in a rabbinical capacity until she was officially ordained in 1998, the first female Rabbi in Tucson. (Sally Priesand became America’s first female rabbi in 1972.)

“I don’t think I really realized how ground-breaking that was here.”

She laughs.

“A lot of time I wasn’t allowed to officiate weddings and funerals. I didn’t fit the … I mean, I wasn’t a man. She pauses, maybe as a way to soften thousands of years of Jewish history, adds, “There is my temperament … Maybe I have more of a free-spirit.”

She did officiate State Rep. Gabby Giffords’ marriage to ex-NASA astronaut, now-U.S. Sen. Mark Kelly in 2007. She later visited her in the Houston hospital, prayed with her and her family, after Giffords survived a gunshot to the head in Tucson while meeting with constituents outside a grocery store. (The shooter, you’ll recall, shot 18 others, killing six, in 2011.) Giffords’ injuries led her to resign from office.

Last year, after 20 years of study with Rabbi Aaron, Giffords became a bat mitzvah at Chaverim, at age 51.

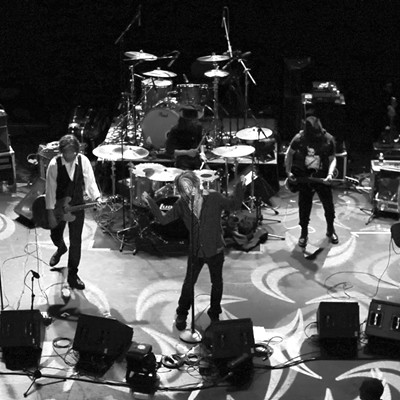

At least one other rabbi calls her a mystic. Yet, when she leads a service, her presence borders that of an entertainer, with accompanying acoustic guitar and singer offering Leonard Cohen poppy versions of klezmer folk songs, kaddishes (prayers), and proverbs, all under an appointed theme of kindness toward others. And when the rabbi sings and chants in Hebrew, her tone tempers the melodies, the harsh edges more mellifluous. (She is a Beatles fan). Even the mundane becomes interesting to an atheist non-Jew like me. (Days later I gathered around a Torah with other confirmation attendees at Chaverim synagogue, an act not exactly kosher in certain Jewish circles.)

For a Jewish rabbi, Aaron is pretty cutting edge. Without diving into a theological history of religion and the three main branches of contemporary Judaism (Orthodox, Reform and Conservative, all of which sort of evolved from ancient Judaism traditions when Jews began to matriculate into the European world after the French Revolution.) What Aaron offers often flies in the face of Jewish orthodoxy. As my Jewish wife points out, she is willing to adapt the religion to the participants instead of making the participants feel guilty for falling short of the religion. She officiates cremation burials, interfaith and same-sex marriages, allows people to become b’nai mitzvah in their chosen gender.

In short, what I understand from Rabbi Aaron’s words and actions is that humanism, a steadfast egalitarianism, centers her life and work, equal parts empathy and awareness. And as a rabbi that also includes environmentalism, feminism, and so many other isms.

It comes down to this, we are all — race, nationality, sexual orientation or gender notwithstanding — one. Basic tenets for all to live by, which is her point, regardless of any religious beliefs, or none at all. She recognizes that hers is not the only authentic path to God, whatever one’s God may be. Or one does not have to believe in God at all.

***

Rabbi Aaron’s parents were not Jewish; protestants, sporadic churchgoers. “My father was a man of God,” she says. “He had direct access to God in that he found God in nature and acts of loving kindness. That’s very Jewish.”

Her parents did lots of volunteering too, and it trickled down. “I was a candy striper, a teen volunteer, helping the sick in hospitals. It really did help me prepare who I didn’t know. Still, I was a 16-year-old kid, I wanted to drive around in my Chrysler.”

She was born in Indianapolis while dad was serving in the Korean War and spent her first six years in Phoenix before the family moved to Tucson. Dad worked for the family business, started by his father, mom a homemaker, “a volunteer person,” taught kindergarten. Her youngest brother was adopted. This boy’s biological mother died of alcoholism and the father, an Air Force man, was drinking himself to death.

“In my family, he is tall. We are not tall,” Aaron laughs. “We are all still very close.”

The adoption, already a stretch for a family with five kids, was an act of pure love. It taught a huge lesson in empathy.

“Empathy, that was part of it; that’s who they were,” Aaron says of her parents, who are now deceased. “I miss my parents so much. They’re a permanent part of my soul.”

At 18, she went with a Jewish boyfriend to hear author-Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel speak.

“It was his testimony, and inner sense of peace,” she says. “I felt like he was only speaking to me. I recognized that I shared his story, it became my story. He’s telling my story, he’s telling our story. That’s it. I had to serve God and the Jewish people. At 18, the seed was planted.”

She graduated Rincon High School and the University of Arizona (English lit major). Fresh out of school, Aaron volunteered for the Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona and taught Holocaust history at Tucson junior highs, brought survivors in to speak to kids.

She later married that boyfriend and had two children. “He was my first love. I had the luck of the draw,” she laughs. “I had a lot of Jewish friends. We met at 13.”

She spent all of her 30s studying to become a rabbi, she couldn’t easily leave Tucson to study because she had two children. She chose the Aleph program, which she calls “a yeshiva without walls.” She mastered Hebrew. Sometimes she’d have to travel to Los Angeles, New York City and other cities, for study and testing, often bringing her children with her. “You have to learn, and then you’re tested, and you have to go to where that person is,” she says.

She is a product of the Aleph program’s so-called “Jewish Renewal” movement, which rose in the late ’60s counterculture, and is an attitude more than anything. Yes, it focuses on spirituality and the more mystical Jewish traditions, but incorporates nontraditional actions, more socially progressive values and social justice.

It is called a “transdenominational movement,” which, Aaron says, means “not being rigid. This is the Jewish people, this is our history. It means this is our way of an exotic life, a beautiful, caring life.”

Among other rabbis, Aaron studied under Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, a pioneer of the Renewal movement who dropped LSD with Timothy Leary and coined the term transdenominational. He taught Aaron to daven, to pray. He taught her the power and depth of stories.

In the meantime, the first marriage, she says, choosing words carefully, “just didn’t work out.”

I ask her if there ever was a sense that your own children felt neglected because you work so much to others?

“I don’t know the answer to that,” she says. “I don’t know the answer. I’ve always been really close to my kids. I know they spent a lot of time in the synagogue. It’s like this job that you’re doing.”

Her husband Jack is a well-read guy, with gray hair and quiet demeanor. He is an ophthalmologist and Rabbi Aaron and they met when she was his patient and have been married more than three decades. (She has accompanied him on many of his altruistic medical missions to developing countries in Latin America and Africa, helping the needy end preventable blindness.)

They each brought two kids to the union and together they had one. They have grandchildren now.

***

Aaron made her first trip to the Polish concentration camps with her husband and stepson just after 9-11. She calls the event life-altering, her story of Buddhist Jews sitting and meditating at Auschwitz, “bearing witness.”

They read names aloud of the murdered. “By the time we left we read 10,000 names in a week.” She remembers some names to this day. “That first time I was fiercely angry. The reality of it.”

She has since made many sojourns with area Holocaust survivors to the annual March of the Living (MOTL), which happens on Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day), a tribute to all Holocaust victims, and includes a march in southern Poland from Nazi death camps Auschwitz to Birkenau.

“I know survivors who wouldn’t go to Poland or Germany, because it is too painful. It takes an amazing courage. On the other hand, it is a march of the living. You’re a living Jew, it can be strengthening. Once you go on the March of the Living, you’re never the same. There is an awakening inside you.”

A major thesis in Aaron’s work so often involves carrying the burden of the Holocaust for the Jewish people, how that connecting and consistent nature passing through generations will always teach. As with Holocaust survivors for whom she has provided guidance, whose families are still broken. “Other survivors became their family,” Aaron says, “aunts, uncles, they didn’t have that. That is another type of family.

“We cannot do it alone,” she continues. “It’s all of our tasks, a sacred duty. What we are doing here is taking this harrowing time, and adding this question: How did it happen?”

She adds, “I’m such a pacifist. But I ask myself, what if the United State hadn’t entered World War II. I do still wrestle with the thought.”

I ask if she has ever been face-to-face with a Holocaust denier. She pauses. “I haven’t. I’m intrigued by the idea.” She pauses again. “I don’t know how I would react. I think it would be dishonor for the Jewish people to actually debate one. Holocaust denial is another form of anti-Semitism.”

The rise of anti-Semitism in the last several years, aided with years of hatred simmering along the surface inside Donald Trump’s White House, and recent vandalism at Arizona synagogues. Hatred is easy, lazy.

“I would never take it off my kippah or yarmulke after leaving the synagogue to go to the grocery store. I’ve been very much more aware now. Is it fear? I think so. I mean just to have that thought process of that kind of hate in the world.”

These days there is an armed guard pacing the front of Chaverim during events.

***

There is a Gun Violence Awareness event called “Wear Orange,” on a Saturday in June in the courtyard at the Southside Presbyterian Church. More than 100 souls, mostly all wearing orange shirts, create a deceptive sugary glow of sherbet ice cream, a juxtaposition not lost on one attendee, a crusty gent I overhear who said, “This all looks so happy!” The tone is quickly shattered when the audience, assembled in portable chairs amid trees and plants, are asked: “Who here are relatives of someone who was murdered?” Many hands reach toward the sky.

Here are parents and brothers and sisters of loved ones murdered with guns. Here are folks tethered to a need to stop gunning down innocents and children, to stop the violence. Rabbi Aaron waits.

Darkness falls and she steps up to the mic after all others have spoken. The long wait is not in vain because she begins with the grace of a true orator, paced, measured, dramatic arches. She hems in thoughts of those in attendance with a nearly musical, five-minute soliloquy that’d do Maya Angelou proud; a mix of prayer and storyteller poetics upholding a topical monologue of murder and gun violence.

“We murder each other by the names we use to reduce people to less than human, to not human, to not us.”

Her words have resonated far more than mere concerned gestures of some well-chosen speaker, and in the final seconds she nails her personal oeuvre. Quoting Lincoln in Hebrew, she offers a religion-transcendent line, which she also translates: “We can fly … with malice toward none, with charity toward all.”

Note: As this story was going to press, Rabbi Aaron suffered the loss of her stepson Joshua Aaron. There are no details to reveal. With respect to the family, we send condolences.