The boy shakes his head and sneers: “It’s the Jesus-fuck man.” He is strolling in pricey kicks toward the brand new Starbucks with three other high school kids, two of them girls in makeup too severe for daylight. They laugh, the unsettling kind of laughter that rises from the well-fed with so much luck and safe shelter on their side. A little life experience will go a long way.

Will shrugs. “Happens all the time.”

It is Will Streit’s loser essence that fuels the kids’ casual cruelty and lazy solidarity. His skin color matters little; he might as well be from Mars. They could never understand — not yet, anyway — the holy-smokes school-to-street vortex of his life, now without a home, and the Dumpster excavations and daily scores for drugs to stay “normal.” The innate inability to establish himself into the acceptable outside world.

They could not yet understand how you can take personal inventory on quests for life meanings and self-awareness through music, art, books and drugs, and how you suffer when such studies lead to you giving up on humanity. Sometimes you wind up, as Will said, “out here like a piece of shit every day,” the only intermediary between depression and glory an addiction supported by selling artful little crosses fashioned from whittled oleander wood and thin copper wire unearthed in dumpsters.

He’s on a corner of a major Tucson intersection that is awash in ugly progress-stamped colors, a Walgreen’s and drive-thrus. He’s dying for a smoke, pops red grapes from an Albertson’s shopping bag.

He talks homelessness, the obvious stuff. How it’s every hell it’s made out to be — all gets stolen so there can be no camp, the elements you taste in your face and feel in your bones, the insults, the starvation, the yearning and depression.

But, he adds, it is a tradeoff. The 36-year-old said he’ll take it over the options. He doesn’t see his lot in life as a problem, more of a negotiation. “I mean I enjoy it [homelessness] to a point. What else can I do? It doesn’t bother me anymore. Even getting upset? Why? All of this,” he adds, waving his arm to the surrounding world, “is so fucking stupid.”

I was startled by the rarity of the sentiment. He elaborates how it is about personal autonomy. “Even having an apartment and mounds of bills can consume you, wreak havoc on your head.”

He is genuinely interested and thankful someone is talking with him about his life. His brain is attuned to the nuances of things. He is very smart, and funny. It is the little things too, the keys to his success, he said, such as there are. He is as dapper as could be imagined in the circumstances, a red pullover sweater, loose-fitting black trousers, a bit threadbare from the miles, road-lived labor boots. His short hair is combed and parted on the side. He sports a perpetual squint and a slight slouch. High cheekbones, narrow chin, handsome in a ’40s Hollywood noir hobo way — like Tom Neal in Detour — crossed with young Kerouac. I tell him this and he is grateful. He’s a fan of trainhoppers, and old-school hobos and the aforementioned. He sides with that (receded) romance of outlaw American folk heroes.

Cars zoom, a siren wails and the crosswalk talks and Will produces from his nearby pile of things a motor from a small vacuum cleaner, which he secured from the trash. He talks the intricacies of it, the turbine, and shows the little copper wire still attached, enough for a few days of new crosses. The entire process of creating the crosses involves hours and hours of work and hustle; the hunt for oleander wood and the copper, the whittling, the wiring.

“I don’t make much for all the effort I put in, know what I mean?”

It’s ingenuity to survive. Like how he’d find framed paintings from thrift-store trash, paint over them white, and sell it on the street. “Upcycling” is how he calls it. “People scrap this stuff and I use if for my art.” If he’s hustling coin on the streets he’s bent to offer something.

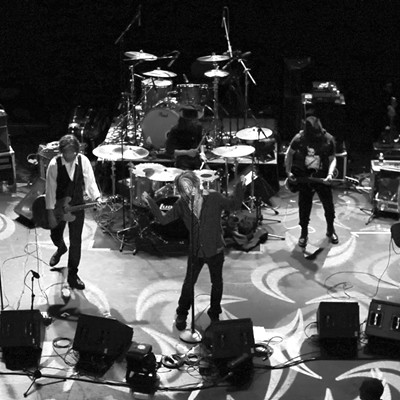

The cross is a potent symbol for him. One cross he holds boasts a chalcedony stone, another obsidian. Others draw on found street rocks with fetching lines. There’s attention to detail and meaning behind the work, which rises from his occult readings and practice. His studies began with a fascination of Christian theology, then mysticism, and next, for example, a raging fandom of Aleister Crowley, the sonics of Genesis P-Orridge and King Crimson.

To drivers on the street he could be some militant Christian, a fanatic peddling homemade Calvary crosses to Believers. The sign he wields to traffic reads, “Local Artist in Need of Art Supplies. God Bless.” It is irony. He needs art supplies, yes, but to Will, he is talking pre-Christianity amulets; the metaphysical, a center-of-the-universe world axis, a crossing of spiritual and physical, an inherently magical symbol. The intricate copper wire holding the crosses together hint too of, he said, Rosicrucianism and masonic orders, and elevated consciousness, which includes aiding others, overcoming obstacles, manifestation. His ongoing study of gems and minerals fits in. It is about his private personal evolvement. He talks of this with an impressive passion that in the moment turns his squint-eyed street fatigue into bodily animation of hands and limbs.

He’s got a code now, a kind of ethical know-how. Things he’s lived through and read whittled to simple certainties: Don’t hurt anyone, share food, and don’t steal. It wasn’t always this way. He learned hard. In and out of prison and jail for a total of about two years, assault, drugs and stealing. He said he is done with incarceration (“I hated it. A lot of ignorant people who just want to fight”) and cops (“they’ll get you for anything out here”). He won’t sell on street medians, he rolls his pile of things in a wheelchair—with a blanket tossed over the top—because shopping carts are illegal.

The Milwaukee-raised Will said he was a depressed kid. The only child of parents who divorced when he was 14, into music and reading, but soon into selling weed, snorting coke. Moved to Tucson at 18 with his mother for her job and attended college, moved to Hollywood where he lived in an apartment off the walk of fame to attend the Musician’s Institute in Los Angeles. There he got guitar playing on, heavy into music theory. He graduated, and is still on the hook for loans. He does not own a guitar now, and misses it. He once had a mad record collection, filled of punk, folk, prog, soul, sold it all for dope.

Heroin and meth got him and whatever family dynamic fell apart. “All I really ever wanted to feel was normal. But when I started using I felt like I got the owner’s manual to my life. Drugs aren’t bad to help you be well, you’re just not supposed to do it every day.”

Will admits his mother tried to help with the addiction, but eventually washed her hands of him. Said he hasn’t spoken to her since 2019. Much longer for his father, now in an old-folks home somewhere. Nor his aunt, to whom he was close. When his grandmother died, a family bottom fell out. He couldn’t call anyone anyway. “Last time I had a phone it was stolen. I passed out for a few seconds and it was gone. If I had a phone, I’d be downloading stuff and studying it.”

He’s rundown on this chilled sunny day, nervous on the amount he needs for drugs. At least he stopped shooting them, he said, too many abscesses, for one. He pulls up his sweater sleeves to reveal old scars, gnarly swirls and gouges. Now it is heroin’s synthetic cowboy cousin fentanyl, which he smokes at night, when the work is done. “I spend a good amount of money on it every day, that and food of course.”

The fake oxy fentanyl-laced “M30” pills from Mexican labs is dirt cheap in Tucson, which Will said he gets for a few bucks a pop. He needs 40 bucks a day for drugs. He charges $5 for a cross, often gets more, sometimes $20. He scores from a homeless guy, and he doesn’t want me to meet or write about that person.

Will said it would still be bad luck to die and talks of his addiction in shrugs of acceptance, his own personal cross to bear, so to speak. Everyone has one.

A woman on foot pulling an oxygen tank along Swan takes a seat in the gravel near Will. She lights up a cigarette. Will waits a moment and hits her up for one. She obliges. He lights it, hits it, and perches it in the gravel. He doesn’t smoke in front of the cars, that would be unseemly to potential buyers.

“And honestly, I don’t take it from the guy with two kids in the back. I’ll try and sell to the Beemers and Benz’s.” He pauses, laughs, “I have some integrity. I am not stealing from anyone.”

He shrugs, half-grins, enough to reveal the broken front teeth, and talks the violence on the streets. “Fights, yeah. Some homeless person will start one over any crazy random thing. Most homeless people are out of control, making messes, so many are all the same, the felons, the thieves. I clean up the street around me. If you look like me people assume I’m that.”

He’s been out here since sunup, it is now 1 p.m. He sold one cross at a reduced rate for a dollar and he also received a pamphlet called Eternal Life. That’s it so far. Like any salesman he said, “it either sucks or it’s super good. It’s okay, I’ll make it up when someone gives a ten for one.”

Thin white dude of about 30 rolls up on a nice carbon bicycle, fixed gear. Will and bike guy exchange a greeting, they’ve known each other, and he begins to roll off again.

“Nice bike,” I say.

“Hey, thanks man,” he said, as he rolls up the sidewalk against traffic.

“Yeah, he stole it,” Will said. Adds, “he only does G. If you do dope you can’t have a job. He has a job and he steals.”

The traffic is relentless. Faces in cars caught at a red light most always feign preoccupation or show agitation when this man in a red sweater selling crosses bends and protrudes his head slightly from the sidewalk for eye contact. He’ll wave, nod. It’s a “hello.”

There’s theater involved, a one-man stage-play, really; the lifting and falling rumble of traffic as orchestral backdrop. There’s some manipulation, a salesperson’s pantomime, which he does well, the grin, the sign, the neat hair and sweater. Will as a street jester secreting unhealable wounds, half-expecting someone to mock him, hawking his crosses with the multiple meanings, a show for survival.

At least Will knows his day will end with his smoked medicine in some dreamy way. The demons squatting inside him gone until sunup, wherever his head lay.