There is a politeness about this kid Tyler Kebo that at first makes me uneasy. It feels like a put-on, the huckster jive of an annoying future politician already well-coached in PR. Timed grins punctuating softball query responses, saying only what he wants to say, rare to elaborate — an exercise in patient indulgence. We sit at a gleaming nonspecific table inside a gleaming nonspecific chain bagelry next to a Walgreens in Tucson’s north foothills. He works here, and is on a break. He wears jeans and a belt, Converse and a company-issued ink-blue shirt.

I am talking to Kebo because it is said by customers and employees that he is a rare kid — kind, officious and diligent, not at all entitled. He wants to work, needs to work. They said I should meet him, which is often all I need for a story.

The senior at Catalina Foothills High School just turned 18. What I found is a self-aware teen, and a gifted musician on a career track who’s deserving of attention. More, Kebo, effects a civility that lifts from a mixed well of almost disquieting benevolence and shyness, a civility that is, I soon discover, an extension of his worldview. He said, with no hint of irony, “It sucks when you mess up an order. I’m a very understanding person. I understand that people go through stuff. You never know what’s going on in their life.”

Soon my jaundiced presupposition of progress — that anyone or thing bounding toward some exalted endpoint is doomed — feels belabored, tired and lazy.

He has worked at Bruegger’s Bagels for two years and today cuts out early from his shift for a show. Too, he just returned from a live audition at the prestigious, impossible-to-get-in Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, and is waiting to hear if he’s been accepted.

I’ve yet to hear him bad mouth another or even swear. He hates talking of himself, yet clues rise in conversation. He is non-religious and a history buff (his fave school subject outside music), he values human diversity and the ongoing discovery of personal identity.

Here is a postmillennial kid who grew up with digital tools at hand, yet he chose a completely analog way to express himself, baroque languages of far-removed eras, from classical to jazz, the polar opposite of TikTok music virals. He lists Rush’s Neil Peart, Questlove, and deaf, barefooted percussionist Evelyn Glennie as his heroes. And to tie a ribbon on what others have said about him, Kebo works harder than about anyone I know, is self-reliant, and turns the idea of teen entitlement to a bromide. His time is precious, between work, school, gigs and rehearsals, it is extremely difficult to speak with him outside of his bagel job.

An average day in Kebo’s life: Wakes up at 5:30 a.m., goes to gym. Returns home, heads to school till 3:30 p.m., rehearsals follow with any one of his ensembles. Then dinner, homework, and two-hour solo practice. Occasionally, Kebo slides in live performances, typically on weekends. He works 11 hours a week, open to close, Sundays at Bruegger’s.

“Days I work are more of my rest days,” he said, his back straight in the chair, hands folded on the table before him. “I’m like this all the time, if there aren’t rehearsals, I’m practicing. Most times I practice by myself.” He pauses, adds, “Sometimes I get burned out.”

One freedom of being a kid is hardly anyone expects much of you. So Kebo built a career in music. He began with piano at age 5, and his dad would play classic rock on the way to school and Kebo would pound along, so he took up percussion at age 7.

I wonder aloud if those who choose to create a career of beating on things are simply pounding off on darker misgivings.

“For me I don’t get the satisfaction off beating the crap out of the things,” he said. “When I was 7 I’d get satisfaction beating the crap out of things. It sounded cool. Now it is about making music that is musical. And I like the pretty stuff more than the heavy rock stuff.”

Anyone great at any art knows it is the sum of countless hours, days, weeks, years spent perfecting the craft, catering to an obsession. It means other things in life suffer.

Kebo is self-aware enough to understand the tenet, what makes him great at one thing makes him suffer at another. “I like to think I’m a well-balanced person,” he said. “I’m not the greatest at communicating with people around me. If anything, that’s what suffers. Since through middle school, I didn’t have the easiest time expressing my emotions. It’s the emotional connection with yourself, the instrument and the people around you, the listeners and the musicians.” He pauses, adds. “I am drawn to the non-verbal way of expression.”

He is so young as to never have endured a heartbreaking split with a girl. He said he has no “real desire or time for a girlfriend now. I just feel like it’s more important that I focus on myself and be happy than pouring all my energy and money into another person.”

In my experience, drummers have been either total stoners or absolutely precise and pedantic about their surroundings, from drums to life. Kebo is neither. He doesn’t drink or drug, saw what it did to one close to him. Said he just “chooses not to.” He seems to live in his head a lot.

The Los Angeles-born Kebo moved to Arizona with his family when he was 3. His bloodline mixes American-Japanese (dad) and European roots, and his face broadcasts warmth and wonder through curious brown eyes and soft skin tones. He lives at home with his father, a real estate photographer who worked in film and television as a cinematographer, and younger sister. The parents divorced several years ago, and it wasn’t easy, he said, but going into family issues is nothing he wants to talk about. “Financially we haven’t been the most stable,” he adds. And he talks of an illness his dad suffered. “Covid really didn’t help.”

He tells me his mother is a digital librarian and both parents are, and have been, super supportive of him.

One thing Kebo had access to is musically gifted and smart people, superstars in their fields. He studied piano with professional Marie Sierra, who introduced him to percussionist Homero Cerón, with whom Kebo studied for a decade. (“I met him when I was little.”) Cerón backed everyone from Tennessee Ernie Ford to Trini Lopez, is a timpanist of Tucson Pops Orchestra, and a retired principle percussionist for the Tucson Symphony Orchestra.

As a sixth grader at Esperero Canyon Middle School, Cerón introduced Kebo to László Veres, founding conductor of the Arizona Symphonic Winds, retired conductor of the Tucson Pops Orchestra, and former principal clarinetist with the Tucson Symphony Orchestra (the Udall Park amphitheater bears his name). Kebo was blown away by the orchestral music and in sixth grade joined the Foothills Philharmonic, a community intergenerational orchestra, under Veres’ direction, and stayed four years. Kebo is a percussionist in the Arizona Symphonic Winds conducted by Veres.

Kebo rattles off names of anyone who has helped him, Veres’s is repeated often. “He was great, he’s been supportive of me since I was little and getting started.”

In fact, Kebo performed Ney Rosauro’s solo marimba concerto, the first, third and fourth movements, “in front of like 6,000 people” in Tucson. The concerto is filled of shifting time changes, complex phrasing concepts, dramatic tensions, anchored on Brazilian rhythms and jazz motifs, South American melodies. Basically, Tucson Pops Orchestra backed Kebo on the marimba. It was his debut as a soloist and was a star turn for anyone of any age, much less a 17-year-old high school junior.

“I was completely surprised they asked me,” he said.

Kebo is also principal percussionist of the Tucson Philharmonic Youth Orchestra and plays in various high school ensembles, steel drum and band. He’s thinking about starting a rock band. In January this year, Kebo manned the drumline with his high school’s Falcon Marching Band in the 5-mile Rose Parade.

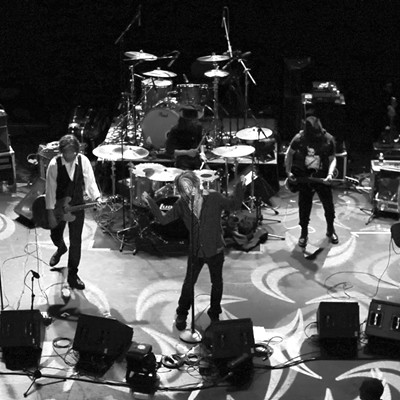

I headed to Catalina Foothills High School theater to hear Kebo play in a student production of “Urinetown,” the Greg Kotis Broadway musical. The winning yarn takes the piss out of capitalism, civic bureaucracy, pay toilets, cops and the idea of a musical itself (“Les Miserables,” for example). The kids tendered a fun performance with exuberance and skill.

The student seven-piece musical ensemble, including Kebo on bass, wind and brass players, a student-teacher trombonist, and a teacher conductor, delivered a rousing, acerbic and whimsical performance of a relatively complex and challenging score, blending musical theater, jazz, vaudeville, and gospel elements.

Kebo, on a full drum kit, filled the theater with a heady little groove. He does not play with the tentative wrists and elbows of a teenager. He plays with grace, an intuition evident in his swing and split-second restraint or push on the beat, matching the intent of the song. He knows, he just knows. You sense that with great drummers, from Stax-man Al Jackson Jr. to Questlove; it is about the greater performance, and Kebo removes himself so as to be fully in; he is a drummer’s drummer at a very tender age. The sight-read beats may cross into math, sure, yet slight fractal-like deviations give it a soul, form definitions of Kebo’s emotional responses, even adding planned ba-dum-dum-splash accents on hilarious dialog. He gets this, completely. You hear it.

His dream is get a career out of all this. “I’d like to study in college, teach high school and become a performer in the Tucson Symphony or even something bigger like the LA Philharmonic.” If the music doesn’t pan out, his back up is, of all things, law enforcement. “I like customer service, interacting with people, the military and law would allow me to help people.”

And if he gets into Eastman? He loved the campus, the people he met, “that was the big pull. I would rather pay some money, and I’d have to work a job, get loans and help from my parents, and go to Eastman, than a full-ride to, say, NAU.”

Back at Bruegger’s, Kebo is called from our conversation to get back to work. It is getting crowded; a line has formed. In a moment he is in service behind the counter with four other employees delivering custom bagel orders. It is fast food, it is a hustle, and the work is arduous, you earn hard every dollar in such places. Kebo hovers around the register, accommodating one hungry customer after the other, the rotund, the thin. His affable banter transcends formality, soothes a mother in charge of an unruly child, relaxes a fussy eater’s impatience. The habits of their lives are not lost on him.

Brian Smith's collection of essays and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections of La Frontera, based on this column, is available now worldwide on Eyewear Press UK. Buy the collection in Tucson at Antigone Books, 411 N. Fourth Ave. You can also pickup his collection of short stories, Spent Saints (Ridgeway Press).